Group Discussion Guide

Table of Contents

What is a Group Discussion?

A Group Discussion (GD) is a structured evaluation technique used by recruiters, MBA programs, and corporate training centers to assess candidates’ communication abilities, leadership qualities, analytical thinking, and teamwork skills. Unlike interviews where you respond to direct questions, GDs require you to participate in a collective discourse where 6-12 participants discuss a given topic for 15-30 minutes.

Why Group Discussions Matter

Group discussions serve as powerful filters in selection processes. Companies like TCS, Infosys, Wipro, and top B-schools including IIMs use GDs to evaluate candidates on dimensions that resumes cannot capture. Research shows that 60% of candidates are eliminated at the GD stage, making it one of the most critical barriers to career advancement

🔍 Explore structured learning resources →

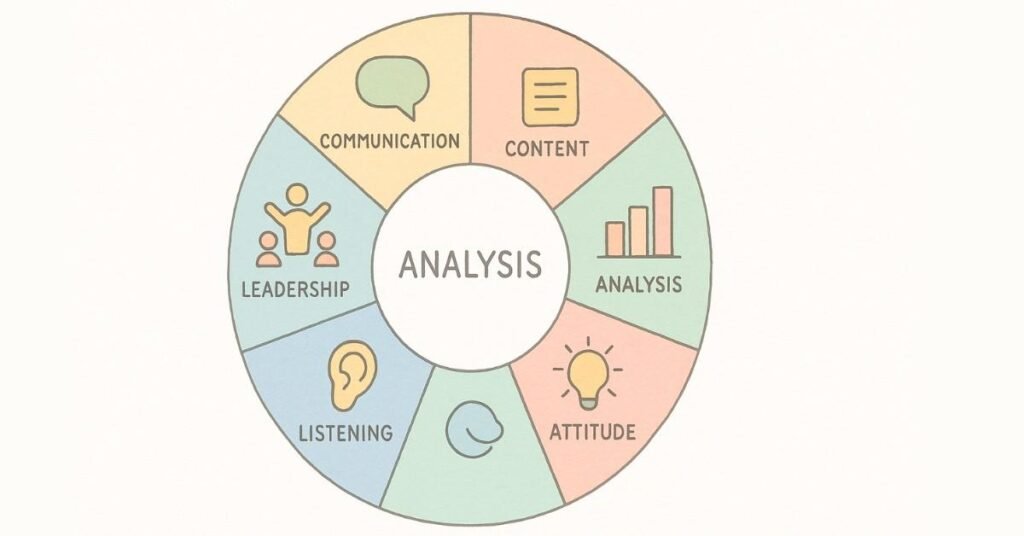

Core Components of GD Evaluation

Communication Skills – Assessors evaluate your articulation, clarity, vocabulary range, and ability to express complex ideas simply. Your verbal fluency and non-verbal cues like eye contact and gestures contribute significantly to your overall communication score.

Content Quality – The depth, relevance, and originality of your contributions matter more than quantity. Evaluators look for factual accuracy, logical reasoning, and ability to present diverse perspectives on the topic.

Analytical Thinking – Your capacity to dissect problems, identify root causes, evaluate multiple solutions, and present structured arguments demonstrates critical thinking abilities valued in professional environments.

Leadership & Teamwork – True leadership in GDs isn’t about dominating discussions but about steering conversations productively, building on others’ ideas, and ensuring balanced participation. Evaluators notice those who help the group reach meaningful conclusions.

Listening Skills – Active listening enables you to respond contextually, avoid repetition, and build cohesive arguments. Many candidates fail because they prepare speeches rather than engaging with the discussion flow.

Attitude & Confidence – Your body language, openness to opposing views, and composure under pressure reveal personality traits crucial for collaborative work environments.

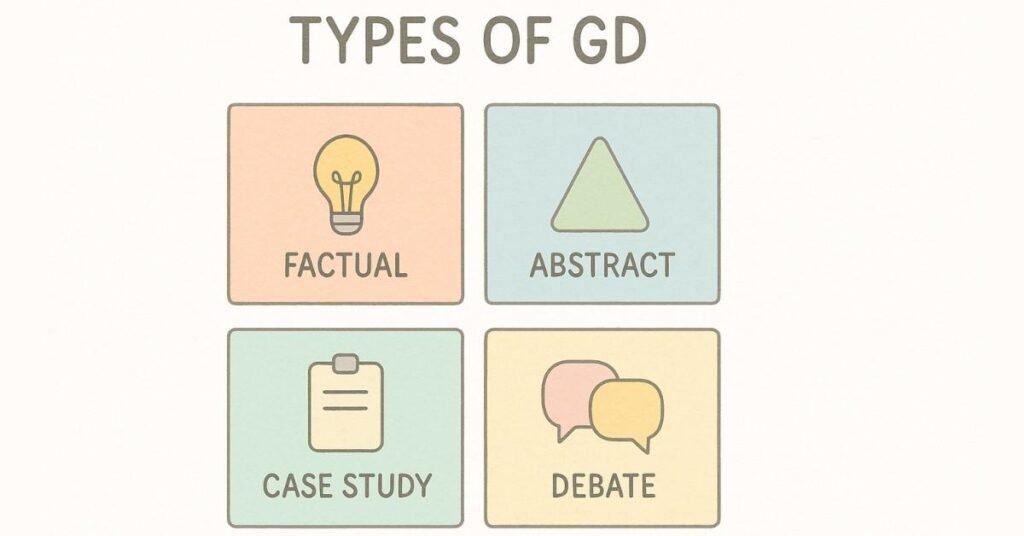

Types of Group Discussions

Factual Topics – These require knowledge of current affairs, industry trends, economic policies, or technological developments. Examples include “Impact of AI on Employment” or “India’s Position in Global Trade.”

Abstract Topics – These explore philosophical concepts, ethical dilemmas, or metaphorical themes like “Is failure a stepping stone to success?” or “Technology is a good servant but a bad master.”

Case Study Discussions – Participants analyze business scenarios, identify problems, and propose solutions collaboratively. These assess business acumen and problem-solving approaches.

Debate-Style GDs – Some organizations conduct GDs where participants are divided into groups supporting opposing viewpoints, testing persuasive abilities and argumentative skills.

The Psychology Behind GD Evaluation

Understanding what evaluators observe helps you perform strategically. They track participation patterns through evaluation matrices rating each candidate on multiple parameters. Contrary to popular belief, the first and last speakers don’t automatically score higher—consistency and quality throughout the discussion matter most.

Evaluators note candidates who monopolize conversations negatively. They value those who create space for quieter members to contribute. Your ability to disagree respectfully, acknowledge good points from others, and synthesize diverse viewpoints into coherent conclusions demonstrates emotional intelligence.

Common Myths About Group Discussions

Many candidates believe speaking first guarantees attention, but premature contributions without substance harm your evaluation. Others think aggression shows confidence, but evaluators penalize interruptions and disrespectful behavior. The myth that only extroverts succeed ignores that thoughtful, well-timed contributions from reserved individuals often receive higher scores than constant chatter.

Some assume GDs have “winners,” but most organizations evaluate individual performances against standardized criteria rather than ranking participants. Understanding this shifts your focus from competition to collaborative excellence.

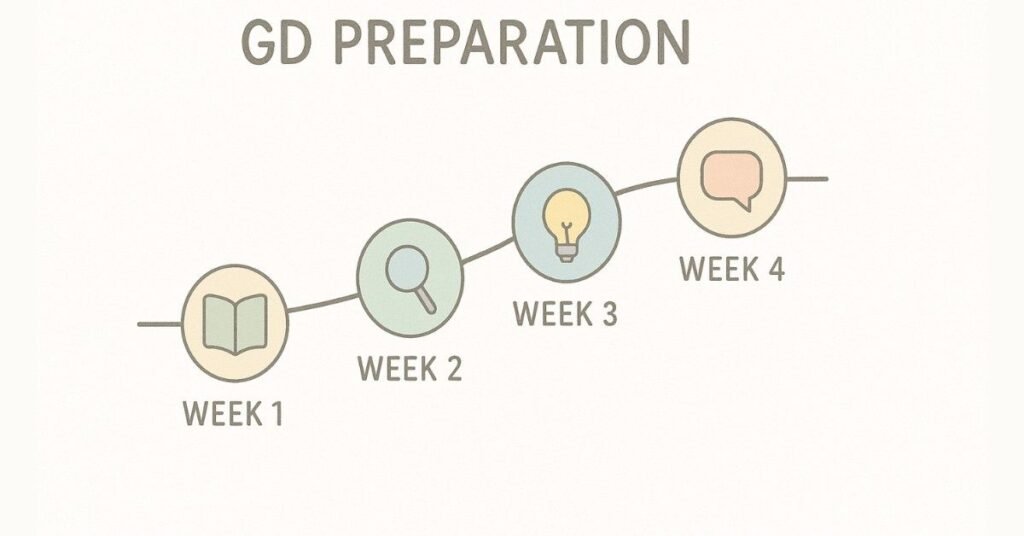

The 30-Day GD Preparation Blueprint

Week 1: Knowledge Foundation – Dedicate the first week to building your content repository. Read newspapers like The Economic Times, The Hindu, or Business Standard daily to stay updated on current affairs. Focus on five key areas: economy, technology, social issues, international relations, and business trends. Create a notebook where you summarize major news stories in 3-4 bullet points, which becomes your quick revision material.

Week 2: Communication Enhancement – Practice speaking on random topics for 2-3 minutes daily without preparation. Record yourself and analyze your speech patterns, filler words (like “um,” “actually,” “basically”), and clarity. Join online forums or platforms where you can engage in written debates to sharpen your argumentative skills. Work on expanding your vocabulary by learning 10 new contextual words daily and using them in sentences.

Week 3: Mock Practice Sessions – Organize mock GDs with friends, classmates, or join online communities conducting practice sessions. Simulate real conditions with 8-10 participants and 20-minute discussions. Request feedback specifically on your entry timing, quality of points, listening skills, and body language. Practice both familiar and unfamiliar topics to develop adaptability.

Week 4: Refinement & Strategy – By the final week, focus on refining your weaknesses identified during mock sessions. Practice the art of summarizing discussions, building on others’ points, and handling aggressive participants diplomatically. Work on your opening and concluding statements for various topic types. Develop frameworks for analyzing any topic quickly using structures like SWOT (Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities, Threats) or PESTLE (Political, Economic, Social, Technological, Legal, Environmental).

📘 Discover more preparation guides →

The Strategic Entry Framework

The Definition Approach – When starting a discussion, begin by defining key terms or setting boundaries for the topic. For example, if the topic is “Is Remote Work Sustainable?”, you might start with: “To discuss remote work sustainability, we should consider three dimensions—economic viability for companies, productivity outcomes for employees, and environmental impact. Let me share my perspective on the economic aspect first”.

The Framework Approach – Position yourself as someone who brings structure by proposing a discussion framework. For instance: “The ‘Make in India’ initiative affects multiple sectors. I suggest we examine three key areas: manufacturing competitiveness, defense production capabilities, and electronics self-reliance. This will give us a comprehensive view”.

The Example-Led Approach – Start with a compelling real-world example or recent news that relates to the topic, then build your argument. This demonstrates your awareness and makes abstract topics more concrete.

The Question Approach – For abstract topics, open with thought-provoking questions that set the discussion tone. For “Technology is a double-edged sword,” you might ask: “Before we debate technology’s role, should we first define what constitutes beneficial versus harmful technological impact?”.

Advanced Communication Techniques

The Building Block Method – Instead of presenting isolated points, reference what previous speakers said and build upon their ideas. Use phrases like “Adding to what was mentioned about automation,” or “That’s an excellent point about data privacy, and it connects to another dimension—cybersecurity”.

The Bridge Technique – When the discussion derails or becomes chaotic, use bridging statements to redirect conversations productively: “We’ve explored the advantages thoroughly; perhaps we should also examine potential challenges to get a balanced perspective”.

The Evidence Integration – Strengthen your contributions with specific data, examples, or case studies. Instead of saying “Many companies are adopting AI,” say “According to recent reports, 65% of Fortune 500 companies have integrated AI into their operations, with Microsoft and Google leading transformative applications”.

The Counterpoint Acknowledgment – When disagreeing, first validate the other person’s perspective before presenting your viewpoint: “You raise a valid concern about job displacement. However, historical precedents like the Industrial Revolution show that technological shifts create new employment categories we haven’t yet imagined”.

Leadership Without Aggression

True leadership in GDs manifests through facilitation rather than domination. When you notice quieter members attempting to speak, create space by saying: “I’d like to hear other perspectives—perhaps those who haven’t spoken yet might share their views”.

Managing Chaos – When multiple people speak simultaneously, step in diplomatically: “We have excellent ideas emerging, but let’s ensure everyone gets heard. Shall we take turns so each viewpoint receives proper attention?”.

Keeping Discussions On Track – If conversations deviate from the topic, guide the group back: “These are interesting tangents, but given our time constraint, should we refocus on the core question about regulatory frameworks?”.

Synthesizing Diverse Views – Demonstrate leadership by finding common ground between opposing viewpoints: “Both perspectives on digital privacy have merit—the need for security and the right to privacy. Perhaps the solution lies in regulated frameworks that balance both concerns”.

Body Language Mastery

Your non-verbal communication significantly impacts evaluator perception. Maintain an open posture with uncrossed arms, showing receptiveness to others’ ideas. Make eye contact with all participants, not just evaluators, distributing your attention evenly around the circle.

Nodding Acknowledgment – When others speak, nod occasionally to show active listening. This demonstrates engagement even when you’re not speaking and encourages speakers to continue.

Controlled Gestures – Use hand gestures purposefully to emphasize key points, but avoid excessive or distracting movements. Keep gestures within your body frame and ensure they complement rather than dominate your words.

Facial Expressions – Maintain a pleasant, interested expression throughout. Avoid showing frustration, boredom, or aggression even when you disagree strongly with someone’s viewpoint.

Topic-Specific Preparation Frameworks

For Factual Topics – Develop a mental template: Current Scenario → Key Stakeholders → Challenges → Opportunities → Solutions → Future Outlook. Apply this framework to topics like “Impact of Electric Vehicles on Indian Economy” or “India’s Semiconductor Manufacturing Ambitions”.

For Abstract Topics – Use the interpretation-example-analysis structure. First, interpret what the topic means, provide real-world examples that illustrate it, then analyze implications. For “Failure is the stepping stone to success,” interpret failure as learning opportunities, cite examples like startups that pivoted after initial failures, then analyze why failure teaches resilience.

For Case Studies – Follow problem identification → root cause analysis → solution options → recommendation → implementation considerations. This structured approach demonstrates business acumen and analytical thinking.

Critical Mistakes That Eliminate Candidates

Entering Too Quickly – Speaking within the first 10 seconds without listening to the topic properly signals unpreparedness. Rushing to initiate shows you’ve prepared generic opening statements rather than engaging with the specific topic. Wait at least 15-20 seconds, absorb what others say if they’ve started, and then enter with contextual contributions.

Over-Speaking and Domination – Candidates who speak excessively believing it demonstrates knowledge actually harm their evaluation. Research shows that speaking more than 4-5 times in a 20-minute discussion, or taking up more than 15% of total time, creates negative impressions. Evaluators penalize dominators because workplaces require collaborative team players, not monologue deliverers.

Interrupting Mid-Sentence – Cutting people off not only appears disrespectful but signals poor listening skills. This behavior escalates discussions into chaos and immediately lowers your teamwork scores. Practice patience by waiting for natural pauses, and if you must interject, acknowledge the speaker first: “That’s an excellent point about sustainability, and building on that…”.

Repetition Without Value Addition – Repeating points already made wastes discussion time and reveals you weren’t listening attentively. Before speaking, ask yourself whether your contribution adds new dimensions, examples, or perspectives. If it merely echoes previous speakers, remain silent and wait for better entry opportunities.

Going Off-Topic – Deviating from the core discussion by introducing tangential issues demonstrates poor focus. Before contributing, mentally verify whether your point directly relates to the topic. If another participant goes off-topic, diplomatically redirect: “Those are interesting considerations, but let’s ensure we address the central question about regulatory frameworks”.

Being Too Passive – While aggression harms evaluations, excessive passivity equally damages scores. Speaking only once or twice, or waiting until the final minutes, suggests lack of confidence or insufficient knowledge. Aim for 3-4 meaningful contributions distributed throughout the discussion.

Treating GDs as Debates – Approaching discussions competitively by trying to “win” arguments creates rigid, combative behavior. Evaluators seek collaborative problem-solvers, not debaters. When someone disagrees with you, respond thoughtfully: “You’ve raised valid concerns about implementation costs. However, considering long-term benefits…” rather than defensively attacking their position.

Understanding Evaluation Matrices

Most organizations use standardized scoring sheets that rate candidates on specific parameters, typically on 1-5 or 1-10 scales. Understanding these matrices helps you strategize your performance.

Communication Skills (20-25% weightage) – Evaluators assess verbal clarity, vocabulary richness, grammatical accuracy, and pronunciation. They also examine non-verbal elements including eye contact, posture, gestures, and facial expressions. Speak in complete sentences avoiding fillers like “um,” “like,” or “basically”.

Content Quality (25-30% weightage) – This measures relevance, depth, factual accuracy, and originality of your contributions. Evaluators note whether you present well-researched information, real-world examples, data points, or novel perspectives. Generic statements without substantiation score poorly.

Analytical & Reasoning Skills (15-20% weightage) – Your ability to dissect problems, identify patterns, evaluate pros and cons, and present structured arguments demonstrates critical thinking. Use frameworks like cause-effect analysis, comparison matrices, or scenario planning to showcase analytical depth.

Leadership & Initiative (15-20% weightage) – Evaluators observe who initiates discussion, proposes frameworks, summarizes key points, manages time, redirects off-topic conversations, and ensures balanced participation. Leadership manifests through facilitation, not domination.

Team Spirit & Listening (10-15% weightage) – Your ability to build on others’ ideas, acknowledge good points, create speaking opportunities for quiet members, and maintain respectful disagreements reflects collaborative potential. Nodding when others speak, making eye contact with all participants, and referencing previous contributions demonstrate active listening.

Professionalism & Confidence (5-10% weightage) – Composure under pressure, respectful language, controlled emotions, and professional demeanor contribute to overall scores. Evaluators notice candidates who remain calm when challenged, accept opposing views gracefully, and maintain positive energy throughout.

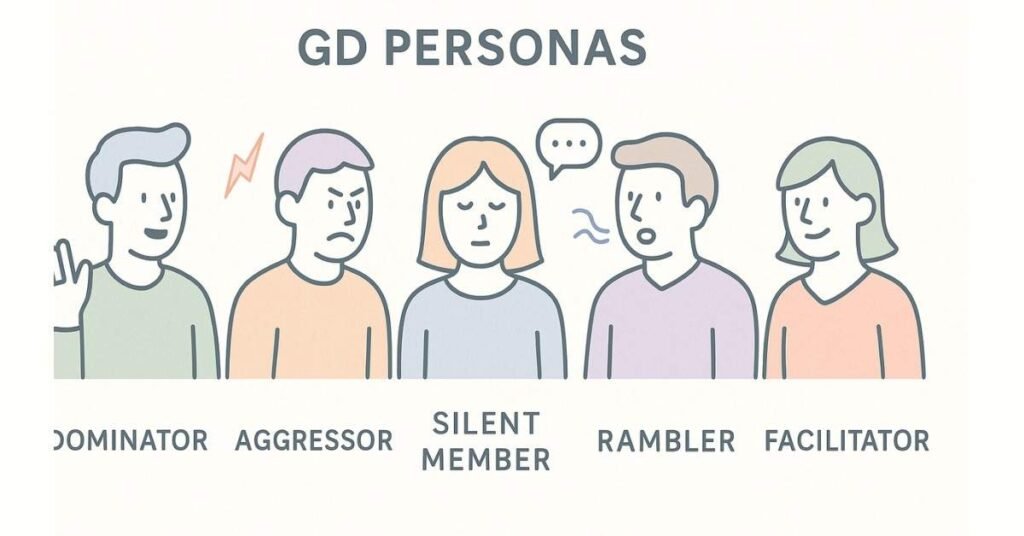

Handling Difficult Participants Strategically

The Dominator – When someone monopolizes conversations, use diplomatic interventions. During their pause, quickly interject with: “Those are comprehensive points. I’d like to hear perspectives from others who haven’t spoken yet.” This redirects attention without directly criticizing them, and evaluators notice your facilitation skills.

The Aggressor – If someone attacks your viewpoint aggressively, maintain composure and respond professionally: “I respect your perspective on regulation concerns. My viewpoint considers different stakeholder impacts, which might explain our differing conclusions.” Never respond with equal aggression, as evaluators penalize both parties.

The Silent Participant – When group members remain quiet, create inclusive environments by saying: “We’ve heard several viewpoints on economic impacts. I’m curious whether anyone sees social implications we haven’t explored.” This open invitation encourages quieter members without singling them out uncomfortably.

The Rambler – When someone speaks lengthily without clear direction, wait for a brief pause and interject with a summary: “So you’re highlighting implementation challenges. Building on that, perhaps we should examine specific solutions.” This diplomatically redirects while showing you were listening.

The Off-Topic Contributor – If discussions deviate significantly, guide them back tactfully: “Those are interesting tangents about global policies. Given our time constraint, should we refocus on domestic regulatory frameworks, which was our original topic?” This demonstrates leadership and time management awareness.

Advanced Performance Optimization Techniques

Strategic Silence – Knowing when not to speak demonstrates wisdom and maturity. If discussions cover points comprehensively and you have nothing substantive to add, remaining silent is better than speaking for the sake of participation. Quality always trumps quantity.

The Power of Summarization – Offering periodic summaries provides immense value: “We’ve explored three dimensions—economic viability, environmental sustainability, and social impact. The consensus seems to be that balanced approaches considering all three are most effective.” This demonstrates listening, synthesis abilities, and leadership.

Asking Clarifying Questions – When topics are complex or abstract, asking thoughtful questions shows engagement and critical thinking: “Before we debate solutions, should we first align on what constitutes ‘success’ in this context?” This positions you as a strategic thinker.

The Bridge Builder Role – When group opinions polarize, finding middle ground elevates your evaluation: “Both views have merit. The regulation advocates emphasize safety, while the autonomy supporters highlight innovation. Perhaps phased regulatory approaches balance both concerns?” This demonstrates emotional intelligence and problem-solving.

Time Management Awareness – Referencing time constraints shows professionalism: “We have about five minutes remaining. Should we focus on conclusions rather than introducing new dimensions?” Evaluators notice candidates who help groups use time efficiently.

🧭 Continue your learning journey →

The Final 2-3 Minutes Strategy

As discussions near conclusion, opportunities arise for high-impact contributions. If no one summarizes, volunteer to consolidate key points: “Let me attempt summarizing our discussion. We identified four major challenges and three potential solutions, with general agreement that hybrid approaches offer the most promise.”

Alternatively, if summary is covered, offer closing perspectives: “An important dimension we didn’t deeply explore is the role of public-private partnerships in implementation. This could be valuable for future consideration.”

Avoid introducing completely new topics in final minutes, as it shows poor time awareness. Also avoid agreeing with everything everyone said, as it appears fence-sitting rather than conviction.

Day-of-GD Best Practices

Arrive Early – Reach the venue 15-20 minutes before scheduled time. This reduces anxiety, allows you to observe the environment, and lets you mentally prepare. Rushing in creates unnecessary stress.

Dress Professionally – Wear formal business attire—for men, shirts with trousers or suits; for women, formal suits, sarees, or salwar kameez. Professional appearance influences first impressions and your own confidence levels.

Manage Pre-Discussion Anxiety – Practice deep breathing exercises. Remind yourself that evaluators expect nervousness and assess your recovery and performance despite it. Avoid last-minute cramming, which increases anxiety without adding value.

Observe Initial Dynamics – As you sit in the discussion circle, observe participant body language and energy levels. Identify who seems confident, who appears nervous, and adjust your strategy accordingly. Position yourself where you can make eye contact with maximum participants.

Listen to Instructions Carefully – Evaluators sometimes provide specific guidelines—whether it’s a debate format, case study analysis, or open discussion. Misunderstanding formats leads to inappropriate participation styles.